This article is originally published by the FAO

In the weeks following Bangladesh’s first recorded COVID-19 case in early March, the Government of Bangladesh initiated a countrywide lockdown to contain the virus’ outbreak.

Vehicles carrying medicine, fuel and perishable items were exempt from the restrictions, but agricultural supply chains were heavily disrupted.

The country’s farmers, most of them small-scale producers, harvest potatoes in March and also begin planting early summer crops like maize, jute, vegetables and pulses.

But from one day to the next, lockdown restrictions prevented farmers from buying agricultural inputs or getting their produce to the markets, said Imanun Nabi Khan, a producer organization specialist at FAO Bangladesh.

“In that first week, the price for perishable products such as milk, vegetables, fruits, fish dropped,” he said.

Leaders of producer organizations, deeply concerned about the health and well-being of their farmers and farm workers, reached out to the Sara Bangla Krishak Society (SBKS) for help in resolving logistics and communication issues.

SBKS immediately tapped into its national network of 55 producer organizations – with over 8 000 smallholder farmers – and its resources to assist.

With technical support from FAO, through the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program’s (GAFSP) Missing Middle Initiative (MMI), SBKS quickly set up 57 call centres, one in each producer organization, throughout northern and southern Bangladesh.

The call centres are also being utilized by non-member neighbouring farmers who are able to obtain fairer prices for their products through the call centres.

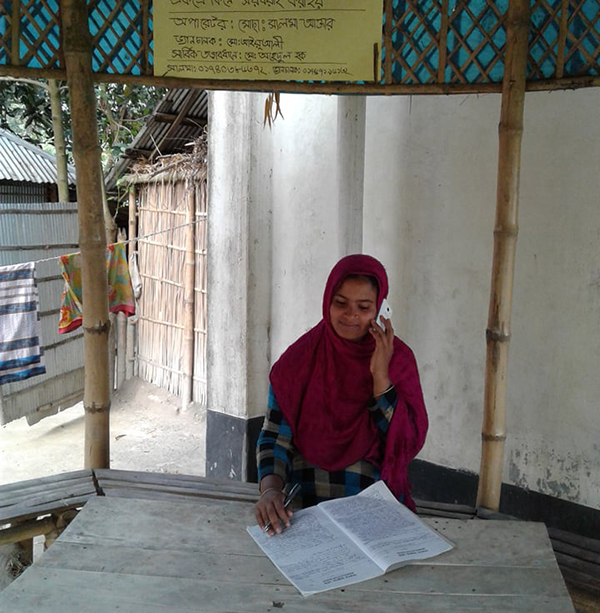

Communication hub

These call centres act as a communication hub between farmers, input dealers, traders and service providers. The centres facilitate the sale of commodities – like milk, eggs, potatoes, vegetables – at a good price and help create effective social media marketing strategies.

Farmers can buy the fertilizers, seeds, animal feed and other agricultural inputs they need to produce their food, and access agricultural advisory services.

Each centre is run by a youth mobile phone operator equipped with every producer organization members’ details and the phone numbers of actors along the entire value chain.

The operator places orders to local input dealers and service providers, negotiating with local traders for fair prices and arranging for collection and drop-off between producers, input dealers and traders. Each call centre has a rickshaw van puller who delivers inputs to farmers and picks up produce to deliver to buyers.

The call centres help keep farmers safe during the crisis by promoting e-commerce and cashless payments, thus lowering the risk of infection.

And they keep farmers, even those in the most remote villages, connected to a broader agricultural community. The centres have become virtual focal points for local coordination and communication, with farmers sharing information, including on maintaining proper hygiene during the pandemic.

SBKS assists in coordinating the call centres as they liaise with local administrative bodies, service providers and producer organizations. Each producer organization has set up a COVID-19 response committee comprising four members, one of which must be a woman.

“Without the call centre, we would have had to throw away our milk, eggs and vegetables. Buying and selling through the call centres is also more profitable.” Hasina Begum

“With advice from MMI, we set up a call centre. It gave us an economy of scale, and we have been able to continue our livelihoods. We do mostly non-cash transactions now and are introduced to the end buyer and seller through mobile interactions. We conduct business transactions by ourselves.” Mst. Morsheda Begum

“Before establishing the call centre, we had problems selling our products and buying inputs. Most of the members, including me, bought and sold items individually but now we think collectively. We can now ensure services for our members through linking with each other.” Md. Oahedul Hoque

Investing in farmers

“The call centres, part of a pilot initiative, involve a small fraction of Bangladeshi farmers affected by the COVID-19 crisis. But the success of the centres is inspiring producers in other parts of the country to follow suit,” said Robert Simpson, FAO Representative in Bangladesh.

“For example, the new USD 500 million World Bank-funded Livestock and Dairy Development Project (LDDP) has adopted the call centre approach to support farmers through its emergency action plan,” he added.

The model is also being studied by the FAO program team, fuelling the development of other strategies to connect farmers to markets in major cities, including Dhaka.

For a low start-up cost, the SBKS and producer organizations have created a stable network, allowing it to absorb more funding and broaden its scope to address other challenges as the crisis evolves.

The SBKS, working with the FAO-MMI and its producer organizations, has identified priority areas to strengthen Bangladesh’s agriculture sector as it adapts to this new reality.

They are looking into developing the call centres as marketing and communication platforms, for example, and investing in traceability, improved food safety and hygiene and better transportation and production equipment.

In Bangladesh, investing in the capacity of farmers to respond, adapt and innovate during times of crisis is yielding good returns.

Find out more on the day-to-day operations of the call centres on this MMI Dashboard. (FAO, 17/06/2020, http://www.fao.org/support-to-investment/news/detail/en/c/1293873/)

Comments are closed